David Hockney 25 at Fondation Louis Vuitton: Drawing Keeps You Young

Sir David Hockney is the greatest living painter. Perhaps not the greatest artist, that is for the experts to decide, but after visiting the exhibition David Hockney 25 at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris, it is hard to argue otherwise. Spanning over fifty years of his career, the show leads you, almost inevitably, to that conclusion. But let us try to bring some order to the emotion.

The exhibition is both anthological and chronological. It opens with Hockney’s early works, and already by the second room, you are face to face with his most iconic masterpieces: A Bigger Splash, Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures), the latter once the most expensive painting ever sold at auction by a living artist. One masterpiece after another. And then, Hockney turns forty.

A collector or art historian might say that this is the peak of Hockney’s artistic expression, and perhaps Hockney would agree. But he does not stop. He keeps going, keeps experimenting. He revisits Fra Angelico, designs opera sets, deconstructs perspective with Polaroids, and unconventional theories like the Hockney–Falco hypothesis.

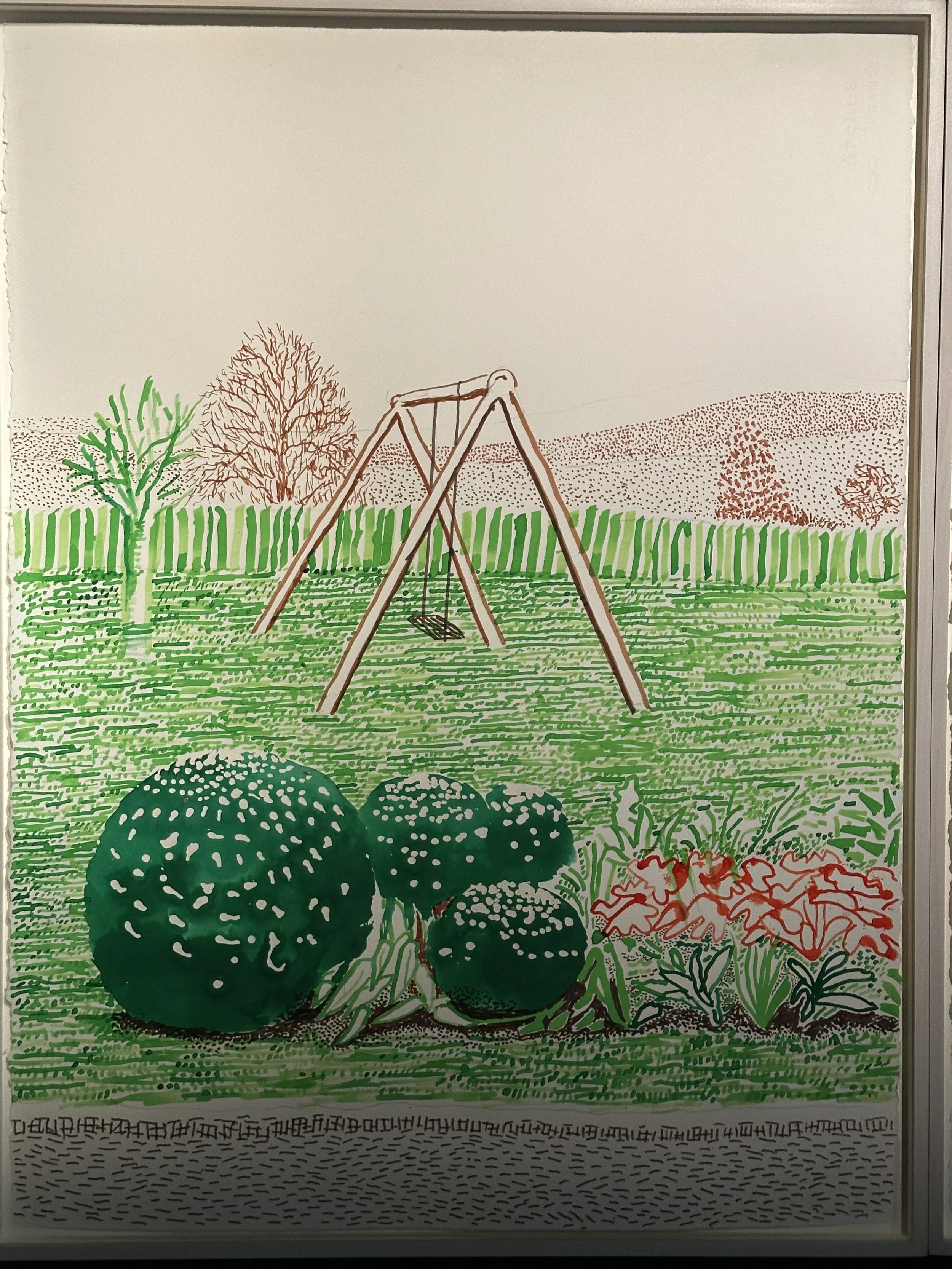

Yet it is the later years that the exhibition explores most deeply, and the ones I want to focus on. His series inspired by Van Gogh has already become a modern classic. But it is the iPad drawings from recent years that truly stand out. First, because they were unthinkable just fifteen years ago. Second, because here we have an elderly artist, well into his seventies, pioneering a new technical frontier. Anyone who has tried to explain cryptocurrency to their parents knows how hard it is to bridge the digital divide. Hockney, on the other hand, becomes a pioneer.

He does it by drawing, his lifelong obsession. Artist biographies often distract more than they help, but to understand Hockney, you need to know this: when something happens around him, he draws. Especially when things go wrong. Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) is also the story of a breakup, sublimated through a softness of color and brushwork that makes all pain dissolve. There is no room for sorrow in a painting like that. Not because it is naively happy, but because it lifts us to another plane.

Likewise, during a depressive episode in the 1990s, in a period marked by the impact of AIDS on the gay community, painting his dachshunds became a form of therapy. And these are not sad dogs. Quite the opposite. Because for Hockney, painting is this: the sublimation of the everyday into something more rarefied, more meaningful.

This detour is necessary to understand his iPad paintings, created during COVID and the isolation of a vulnerable subject. Nature here is not depicted with harsh realism. These works do not aim to replace reality. Painting becomes, instead, an exercise in living. He cannot help but filter the world through his inner eye, where even a dull parking lot becomes a blooming garden.

What emerges is that Hockney’s gift is not just his eye, but his hand. This daily, repeated process is not anti-intellectual. It does not switch off the brain. Rather, hand and mind are perfectly aligned. Asking which comes first, like the chicken and the egg, is pointless. They are now the same.

This exhibition is also a celebration. We are witnessing a great artist at the end of his career and the height of his fame. Will his work stand the test of time? I believe it will. In an era where painting has never mattered less, Hockney reminds us that art is still about drawing and color. It was on cave walls forty thousand years ago, and it probably will be forty thousand years from now.

Photography, with which Hockney has always engaged, never managed to erase the reasons we paint. His works transport the viewer to another plane, with him. With all due proportions, Hockney owes much to Piero della Francesca, not just stylistically. Piero lifts us to a spiritual realm. Hockney brings us into his emotions, which suddenly become ours. And in that moment, we rediscover the joy of watching a thunderstorm as a child. Maybe it is not much. But today, it is more than enough.